The Burning of the Rice

Stacks

Translated From The Japanese

By Taeko Kondo

Original Title: The Burning of the Rice Stacks

「いなむらの火」

Writer: Nobuo Sakurai

桜井信夫

Picture: Ryokichi Ozawa

小沢良吉

Published by Asunaro Publishing Company

あすなろ書房

Forward

This true story was originally written as “Living God” by Latcadio Hearn. Tunezo Nakai later

adapted the story as a tale that appeared in a textbook of primary school in 1937. From1937

to1947 this story was held in high esteem as an anti-disaster drill for children.

In 1854, the big earthquake, known as Ansei-no-daijisin, occurred and a tsunami swallowed the

entire village of Hiro (town Hirokawa, Wakayama prefecture). The lives of the villagers were

saved by prompt evacuation to the safety place thanks to Goryo Hmaguchi.

Today, this

story has a worldwide impact as it tells us about the nature of a tsunami and the

importance of prompt evacuation in the face of such as disaster.

A former headmaster at Taikyu junior high school, Kaoru Simizu writes in the 12th edition of

“The History of

Earthquakes”(Rekisi Jisin 12gou).

“Under the wartime control, I don’t know any other story that was so impressive as this. I clearly remember that I was moved by Goryo’s enthusiastic humanity and noble character. However, it is a pity that the original famous story, Inamurano-hi, covers just a part of Goryo’s life and only a few people know about the greatness of the rest of his life."

As Kaoru Simizu mentions, Tunezo Nakai describes Goryo only as the savior of his village from a

tsunami. But Goryo invested all his money in

building a levee and founding a private school, Taikyu-sha, for the village youngsters.

His foresight in seeing the arrival of a new

era and contribution to learning should be recognized.

My translation of Inmura-no-hi by Nobuo Sakurai describes Goryo as not only a saviour but also

as a man of foresight and devotion.

Goryo was the seventh master of a famous Yamasa soy sauce brewer and later, he became the firstPresident of the Wakayama Prefectural Assembly.

In summer, 2005

Taeko Kondo

まえがき

この物語は実話で、元になったのはラッカディオハーンの「生き神様」です。それを中井常蔵が「いなむらの火」として書きあげものが、1937年小学校国語教科書に載りました。1937年から1947年まで、この物語は防災教育小学校国定教科書「いなむらの火」として高く評価されました。

1854年安政元年大地震が発生し、広村(和歌山県広川町)を大津波が襲い、村は津波に飲み込まれてしまいました。けれども、浜口梧稜の即断で村人は急遽安全な場所に避難したため、村人の命は救われました。

今日もこの物語は防災教育の模範として、世界的な評価を得ています。津波の性格がどんなもので、大地震の後やって来る大津波に備えた緊急避難の大切さを教えてくれるからです。

元耐久中学校の校長、清水勲氏は「歴史地震」第12号で次のように述べています。「戦時体制下、これほどまでも当時の子供の心をとらえてはなさなかった五兵衛(梧陵)の崇高な人間愛・郷土愛は今も鮮明に脳裏にやきついている」「ところが、この物語には実話があり、五兵衛(語稜)のそれ以上について知る人は案外少ないようである」

清水氏も述べているように、中井常蔵は五兵衛(梧稜)を大津波から村人を救った偉人として描くに留まりました。浜口梧稜の偉大さはそれのみに留まらず, 私財を投げ出して堤防を築き、村の若者のための学舎、耐久舎を創立したことです。

堤防を築くことによって、村の将来に備え、きたるべき新しい時代に備えるには農民といえども、漁民といえども学問の必要性を先見の明をもって見据えていました。私は、浜口梧稜のこうした先見の明と献身的な実行力とを高く評価したいと思い、桜井信夫作「いなむらの火」を英訳しました。

浜口梧稜はあの有名なヤマサ醤油の7代目の社長でした。のち、和歌山県議会初代の議長になった人でもあります。

2005年 夏

近藤多恵子

The Burning of the Rice-stacks

After the earthquake

There was a small village on the seashore. It was twilight in autumn. The people in the village were busy with the final harvest. When the autumn harvest was finished, there would be a

festival and young men were preparing for this event.

The seashore was shaped like a deep creek and waves lapped peacefully on its shore. From the

top of the hill located on the innermost part of the shore, the entire village and the creek could

be seen.

Goryo Hamaguchi was looking over the shore from his house on the hill in the twilight. He

muttered to himself, “That was a strong earthquake, but it seemed to have no serious effect on

our village.”

That day was hot and humid different from the usual evenings when a cooler wind blew from the

sea. The earthquake had stopped after a few tremors that had caused the pillars of the house to

creak . The setting sun was sinking below the horizon and it was getting dark.

Goryo was looking across the sea for a long time. He could not tear his eyes away from the sea

because he felt that something would happen.

“Oh! What’s that ?” He cried suddenly at an unusual sight and moved towards the brow of the

hill in order to see the scene more clearly. Something unusual was happening off shore. The

waves was running away from the far-off shore instead of lapping gently upon it.

The sands of the shore were getting wider and wider. He had never seen such a tide so far.

Unintentionally, he cried : “Oh! That rock has emerged !” He also saw that a few fishermen were

running after the ebb tide as if they were children again. Perhaps no one knew about such an

unusual ebb tide except these fishermen.

Suddenly Goryo shivered all over with fear. He remembered a tale that his grandfather had told

him when he was small. He immediately entered the house and shouted: “Touch! Light the

touch!” Men and women were preparing dinner, and were surprised and upset at Goryo’ s

threatening attitude. With great irritation, he cried again, “Light the torch! Hurry up!” and

rushed out of the house carrying a blazing touch.

Near Goryo’s house, there were piles of rice stacks ready for threshing. He lit one of the stacks and then hurried from one to another, setting fire to them all.

“Why on earth are you doing that? What’s wrong with you, setting fire to these stacks of rice!”

One of his servants ran after him and tried to stop him, but he ignored his pleas and shouted,

“Shut up!” The servant cried, “Oh, no! You must be mad!”, but Goryo retored: “No, I am not

mad ! You’ll see!”

The blazing fire lit up Goryo’s face. He looked full of confidence and very stern. The servant

broke down and wept at the sight of Goryo, crying “Oh! Our efforts will all be in vain!”

After he finished lighting all the rice stacks, Goryo stood on the brow of the hill, the blazing touch

still in his hand. “At last! The villagers have noticed.” he said.

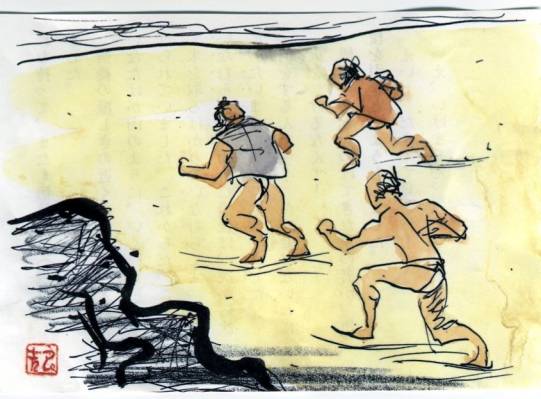

Goryo saw that the young men were running up the hill with the children following them.

“Goryo’s house is on fire! Put out the fire!” everyone cried. The fire bell was clanging violently.

The piles of rice stacks blazed and lit up the dark sky. The young men who were first to arrive

tried to put out the fire, but Goryo stood in the way and cried: “Leave alone! Have all the

villagers come here as quickly as possible!”

One after another, the whole village climbed the hill to Goryo’s house. Men and women, young

and old, as well as babies, followed. It was a custom then that, the moment something happened,

all the villagers would rush to Goryo’s house.

The tale dates back to the autumn at the end of Edo in 1854, in Hiro, Kishu Wakayama Han.

A

tsunami sweeps the village

Goryo and the villagers stood face to face watching the blazing rice stacks. None of the villagers

understood Goryo’s behavior. The servant broke down and wept, rising again to cry, “He lit the

stacks on fire! He must be mad!” Goryo insisted “ I lit the fire! But I am not mad!”

“ Everyone is here, aren’t they?” Goryo asked. “Yes, everyone is here.” answered one of the

villagers. Goryo sighed and cast his eyes in the direction of the sea. The wind blew suddenly and

there was a loud roar from the depths of the earth.

“Look over there! ” cried Goryo. On the far dim horizon, huge waves came surging towards the

shore like the shadow of a coastline. The line thickened as they watched. “Tsunami!” cried the

villagers

one after the other.

Instantly

the huge waves reached the creek and crashed violently against the shore and

the hill.

In

shock, the villagers jumped back involuntarily. They squatted on the ground with their eyes

closed. The sight was too terrible to watch.

The tsunami engulfed the whole village _ the shore, the houses and the fields. No trace of the

village remained and the astonished villagers could not find any words. Their dear houses and

fields had collapsed and been swept away. Only scares on the seashore remained.

The weakened tidal waves went back and forth several times until the sea calmed. The rice stacks eventually burned down and only the blazing torch lit up the frightened villagers’ faces. Goryo began to speak: “This is why I fired the stacks. Looking across the sea, I was afraid that a tsunami would hit the village. I wondered how to rescue you from the imminent danger. It hit me that a fire was the best way to pay all your attentions and promptly lead you to the safety hill.”

He looked back his servant with a smile and said “Now, you understand that I am not mad, don’t

you?”

One of the villagers knelt down and said, “ You saved my life!” Tears welled up in his eyes.

Others also came to and knelt down in gratitude, some of them expressed their gratitude with their hands pressed.

Building a levee

The big tsunami that swept over Hiro village also attacked throughout the Kishu area, including

Osaka bay. The casualties caused by the earthquake totaled 3,000and 15,000 houses were washed away. A total of 10,000 houses were destroyed and 40’000 others damaged. Some 6,000 houses were burnt down.

This is recorded as the biggest earthquake in Japan and is called Ansei no dai-jisin. Goryo saved

the life of the entire Hiro village.

In the morning following that dreadful night, the villagers urged themselves to try and rebuild

their village. However, they were at a loss as to where to start as they had nothing at all.

Hamaguchi Goryo’s family had been wealthy soy sauce brewers for generations. Goryo was in his

mid-thirties and the seventh master of his family. His style, however, was not to make money,

but to contribute to the people because he always thought, “I owe what I am today to the people.”

He foresaw that, scores of years later, the feudal age would be replaced by the Meiji era. In 1852,

two years before the tsunami hit the village, Goryo founded a private school, Taikyu-sha, for the

village youngsters.

He was always of the opinion that, even the village lads who were engaged in farming or the

fishing should have an education. Without learning, they would not be able to cope with the

coming new era.

Taikyu-sha meant: “Any hardships the lads face, they must overcome and move ahead.”

Goryo talked with the boys at the Taikyu-sha about the restoration of the village and pondered,

“No matter how hard the villagers work, it will be impossible to recover the destroyed fields in a

year or so. To begin fishing again, people need fishing boats. Money is the first consideration for

everything. Does anyone have any good ideas?”

This problem crossed his mind whenever he looked over the village from the hill or walked along

the seashore. “Even if the village restored, someday in the future a

tsunami might hit us again.

It will end up a repeated tragedy.”

Goryo took a handful of sand. The grain spilled out between his fingers. Goryo looked over

Tensu beach.

An idea

hit him and he muttered himself:

“That’s it! I’ll construct a

levee ! I’ll plant trees that

will

help strengthen the bank. And if

the villagers undertake this work, they can earn some

money.”

His idea

was realized eventually as Goryo started his new enterprise. Rather than giving money

to

charity, he paid the villagers to build a levee. This was rewarding, both for the people and for

the

village.

Four years passed. The levee was built perfectly, thanks to the hard work of the villagers. The

houses and fields, too, had been built.

Goryo Hamaguchi became the first chairman of the Wakayama Prefectural Assembly in the Meiji

era.

It has

been more than100 years since the levee along Tensu beach was constructed. Trees have

grown tall and thick, with firm root.

The revee protected the village against the tsunami caused by both the Tounankai earthquake

in1948

and the Nankai earthquake in

1946, both of which registered more than 8.0 on the Richter

scale.

Today Taikyu junior high school in Hiro and the senior high school in Yuzawa are the successors

of the Taikyu- sha established originally by Goryo.